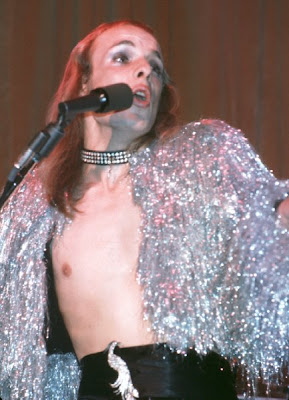

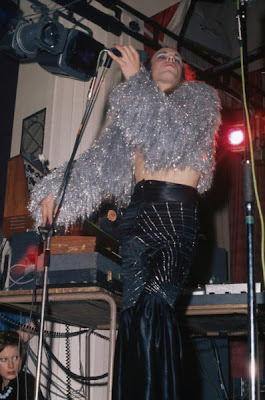

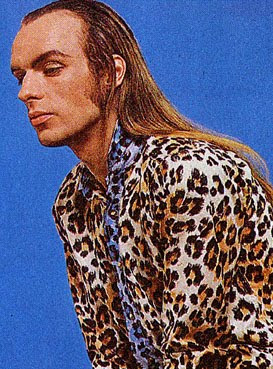

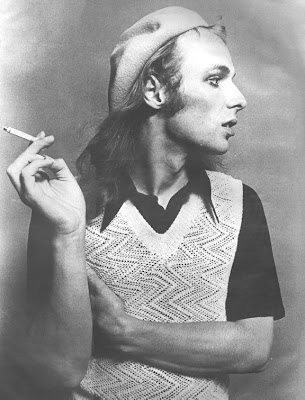

A brilliant conceptualist, a founding member of Roxy Music, and a self-described "non musician," the appallingly prolific Brian Eno is probably best known as a producer — he was behind the boards for some of the best albums made by David Bowie, Talking Heads, Devo, and U2 — and for having coined the phrase "ambient music." A pity, that; Eno has also made wonderful music of his own, recording entrancing tunes with ingenious counter melodies that should have been hits, but weren't.

Pop content is just one component in the Eno catalogue and melody doesn't seem to interest him half as much as sound itself. Consequently, trawling through the Eno catalogue can be as frustrating as it is rewarding, especially as his later albums tend more toward music that seems airy, empty, and maddeningly diffuse.

In that sense, perhaps the best way to approach the Eno oeuvre is by forgetting chronology and diving in with the box sets. I: Instrumentals is a delightful omnibus of sound sketches, studio experiments, and sonic art. Some of it is from collaborations with Bowie, avant-pop trumpeter Jon Hassell, minimalist composer Harold Budd, King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp, or the German electro group Cluster; some is from solo work using his own keyboards or session musicians. Invariably, Eno finds a certain idiosyncratic element in the sounds produced, and tickles them out. When his teasing tends toward atmospheric stasis, the results are generally dubbed "ambient" — sort of like New Age gets an MFA. But not everything there falls into that category; some tracks, such as "Energy Fools the Magician" or "Chemin de Fer," are as catchy and well-crafted as any pop single.

The second box, II: Vocals, has far more of that, and relies heavily on Eno's early albums. Applying what he learned about pop subversion from his tenure in Roxy Music to the revisionist aesthetic of new-wave rock, songs such as "Baby's On Fire," "King's Lead Hat," and "Here Come the Warm Jets" boast all the hook-driven appeal of hit singles, yet without the heard-it-before predictability of conventional pop. Eno rarely took the conventional give-the-singer-the-melody approach, however, and on a number of tracks, the vocal — which may be song, or speech, or some "found" bit of a movie or radio broadcast -- is just part of the overall sound, often almost incidental to the instrumental parts.

For fans of his vocal music, the key Eno albums are Here Come the Warm Jets, Taking Tiger Mountain (by Strategy), and Before and After Science. It may be easy to hear in both an anticipation of punk and an echo of Roxy Music in the arch clangor of Here Come the Warm Jets, but what shines brightest is the offhand accessibility of the songs. It hardly matters whether he's playing with style (as with the doo-wop undercurrent to "Cindy Tells Me") or fooling with form (the portmanteau construction of "Dead Finks Don't Talk"); the melodies linger on. Listening to it now, the album seems almost a blueprint for the pop experiments Bowie (with Eno producing) would conduct with Low.

Taking Tiger Mountain (by Strategy) is just as pop-friendly and eclectic, but shies away from the abrasive textures of its predecessor, swapping distortion and dissonance for blurred edges and open-ended harmonies. Not that the album is entirely without teeth, as there's an itchy aggression to the breathless "Third Uncle" and an ominous urgency to the latter half of "The True Wheel." But Eno keeps such snarls on a tight leash; far more typical is the dry wit of "Back in Judy's Jungle."

But it's Before and After Science that stands as the greatest of Eno's "pop" albums. A nearly perfect album, it frames Eno's melodic instincts in every imaginable way, from the chilly funk of "No One Receiving" to the irrepressible vigor of "King's Lead Hat" (an anagram for Talking Heads), to the dreamy cadences of "Here He Comes."

After sitting out the 1980s, Eno returned to the pop form in 1990 with the brittle, uneven Wrong Way Up. Recorded with John Cale, it's a good attempt at recapturing the old magic, but frankly Cale's intense artiness undercuts Eno's instincts. My Squelchy Life was originally intended as the follow-up, but after making advance copies available to the press, Eno withdrew the album (which is now available only on bootleg). Instead, the unexpectedly funky Nerve Net became his next pop effort, and it mostly fizzles. Perhaps sensing the tenor of the times, Eno puts more effort into making good grooves than in writing memorable melodies, and while the resulting tracks are full of good energy and interesting sounds, they lack the hooky good nature of Before and After Science.

Then again, after Eno's having spent most of the previous decade releasing album after album on which texture was king, what were we to expect? Although some critics have derided his instrumental albums as being a sort of high-concept mood music, it wasn't mood he was interested in; it was atmosphere. On these discs, he took an almost functional approach to music, manipulating its sonic power in the same way a painter or interior designer might manipulate the power of light, color, and form.

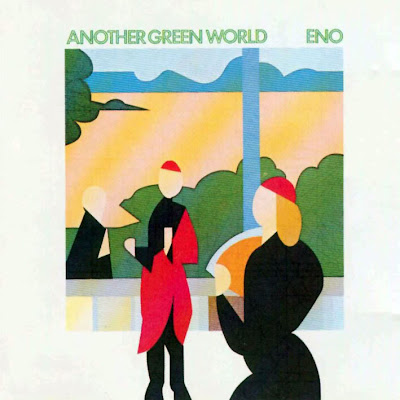

Eno began moving in that direction with Another Green World. Here, he uses the studio itself as an instrument, molding directed improvisation, electronic effects, and old-fashioned songcraft into perfectly balanced aural ecosystems such as "Sky Saw" or "St. Elmo's Fire." Initially, he referred to these quiet soundscapes as "discreet" music, and on Discreet Music (a wry deconstruction of "Pachelbel's Canon in D") demonstrates his basic tools: minimal melodies, subtle textures, and variable repetition. Around this time, he had also been collaborating with the German synth duo Cluster on a pair of moody, coloristic electronic albums, selections from which may be found on the Begegnungen and Begegnungen II compilations. But it was Music for Airports that finally codified these experiments into an aesthetic, and even provided a label for the sound: ambient music.

As much as Eno understands about psycho-acoustics and the relationship between what is heard and what is merely sensed, the largely functional (and mostly tuneless) nature of the music limits the listening pleasure of subsequent ambient releases, such as On Land, Apollo, and Thursday Afternoon. (Eno also produced albums by other artists for his ambient series: both Harold Budd's rich, moody Plateaux of Mirror and Laraaji's shimmering Day of Radiance are slightly more energetic and engaging than Eno's own efforts.)

There were, of course, releases that didn't carry the ambient tag but seemed part of the same musical subspecies. The three volumes of Music for Film work very much on the same principle as the ambient albums, and feature some of the same collaborators. Likewise, there's an extreme emphasis on atmosphere in the spacey Shutov Assembly, the contemplative Neroli, and the delicately textured Drop.

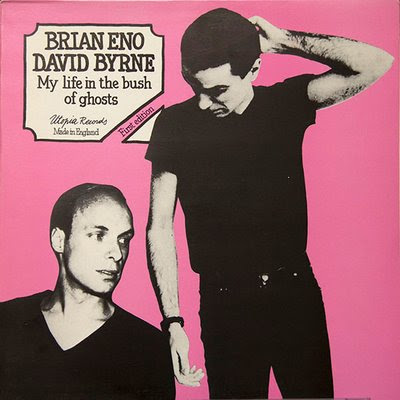

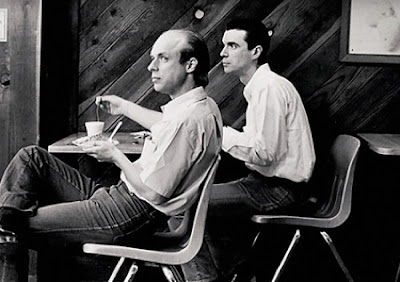

Meanwhile, Eno continued to collaborate with others. My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, which takes its title from Amos Tutuola's novel, was recorded with Talking Headman David Byrne, and offers some insight into the cut-and-paste approach to groove the two applied while making Talking Heads' Remain in Light. Its "found art" approach to vocals (however scrupulously footnoted) is an acquired taste, but in hindsight it sounds like a true forerunner of hip-hop sampling. Spinner, recorded with former Public Image Ltd. bassist Jah Wobble, boasts gently insistent grooves and strongly Middle Eastern flavors, elements Eno had flirted with on the earlier Ali Click.

Eno also worked with the German DJ Jan Peter Schwalm. Their first collaboration, the Japanese-only Music for Onmyoji (literally, "Music for the Fortune-teller"), is a double album combining one disc of conventional, deftly crafted synth-scapes with a disc of manipulated and collaged recordings based on gagaku, the ancient traditional music of the Japanese Imperial Court. Drawn From Life is rather less exotic, relying on Western instrumentation and household sounds to generate a rich, surprisingly evocative sonic tapestry celebrating the rhythm of day-to-day life (hence the title).

There's a third stream to Eno's catalogue that isn't represented by a box, and that's his "installations." These are sound sculptures created for specific environments; usually instrumental, they are not compositions in the traditional sense, with a beginning, middle, and end, but are open-ended constructions designed to go on indefinitely without looping or intentionally repeating the material. (Opal is Eno's own label, and these discs are available online from www.enoshop.co.uk.) Some, such as Kite Stories or Compact Forest Proposal, for instance, come from environmental pieces in which multiple CD players, loaded with multiple discs, provide layers of music from varied locations. Obviously, the CD experience can only approximate the installation. Others, such as Lightness and I Dormienti, are more conventional ambient pieces. Perhaps the most interesting is January 07003: Bell Studies for the Clock of Long Now, which treats, toys with, and manipulates the sound of bells, a wonderfully transformative piece that provides new insight into everyday chiming.

More Blank Than Frank and Desert Island Selection are best-of albums emphasizing material from Warm Jets through Science. And Curiosities, Vol. 1 is essentially a collection of leftovers, tracks deemed by Eno too interesting to discard, but too singular to be included elsewhere. Completists only.

By the 1990s, Eno was an established voice in a range of contemporary music. In Low Symphony, composer Philip Glass spun off themes and variations of Bowie's Low, a work indelibly marked by Eno's stamp; ambient techno bands like the Orb and Irresistible Force owed an obvious debt to Eno. He has also long been interested in other media, his video installations having been exhibited at the Venice Biennale and the Pompidou Centre in Paris, and his 1996 autobiography, A Year (With Swollen Appendices) having provided an index of his omnivorous interests. Eno continued to expand the vocabulary of music into the new millennium, composing for video games and producing albums by artists ranging from veteran Paul Simon to newcomer Coldplay.

In 2004 he teamed up with old friend Fripp for another ambient collection, and in 2006 he celebrated the 25th anniversary of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts with Byrne. The latter project had feet in both the past and future, as the marketing plan included a Website wherein fans of the classic work could legally download multi-tracks of two songs, remix them and then repost them for others to hear. That same year, Eno released the visual work 77 Million Paintings, a DVD/software package offering computer screens a constantly evolving painting with an ambient-music background. In 2008, after nearly 30 years, Eno and Byrne again reconnected for Everything That Will Happen Will Happen Today, a follow up of sorts to My Life in the Bush of Ghosts.

As a composer, producer, keyboardist, singer and multi-media visual artist, Eno is responsible less for a new sound and look in pop than for an entirely new way of thinking about music — as an atmosphere, rather than a statement, an experiment in sound, rather than a virtuosic expression. Combining the cerebral qualities of European high culture with the technological outlook of a futurist, he also has been responsible for an aesthetic movement that incorporates both Western and Third World sounds.

Wiki info can be found here http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brian_Eno

Various Video Of Brian Eno

Roxy Music With Brian Eno - Grey Lagoons Live

Brian Eno - Music For Airports Interview

Brian Eno & David Byrne "Strange Overtones"

Brian Eno - Interview/Lecture

Brian Eno on Songs

Rock On Music Lovers!!

-Stereo

If you liked this article then make sure you subscribe to the feed via RSS

It's Free. You can also follow me on Twitter too!

Check out the Retro Rebirth Design Catalog

No comments:

Post a Comment